Stopped

at "No sign. Gone. What matter?" (Gabler 4.190) (Penguin p. 72)

This

episode start the beginning of book II (Ulysses is divided into three books)

and is much more straightforward and easier in tone than the previous one. We

meet Mr Leopold Bloom in the morning preparing a breakfast tray for "her"

(presumably his wife) and getting ready to leave the house to get a kidney for

himself.

Before

leaving for the butcher's he asks her if she wants anything (a moan is all he

gets in reply and the jingling sound of the bed as she turns, which makes him

think he must finally have those springs mended). He then picks up his hat,

checks the hat-band with the inscription "Plasto's high grade ha" (with

the T sweated off from frequent wear) assures himself that the "white slip

of paper" is still inside his hat-band, "quite safe", and that

he has his potato (4.69 ff.). We don't know at this point what the paper and

the potato are about. He doesn't have his house keys since he's left them in

his other trousers but he can risk leaving the house without them just for the

moment.

At Dlugacz, the

butcher's, Bloom waits for the customer who's being served to finish her

purchase (it's the next-door neighbours' the servant girl) and observes her

rather chapped fingers and her "vigorous hips", whose sight he rather

likes (4.148). In fact, he's hoping to get a chance to follow her on the way home and watch her secretly if the butcher serves him fast enough. Unfortunately (and here's

one of life's many little frustrations already) the girl heads in a direction different

from home.

A few comments about this chapter:

Consider its opening. The first

thing we learn about a character, Mr Bloom, is what he likes to eat, and he eats

"with relish". For a moment, however, we may be misled:

"relish" could at first be understood to mean the sauce, and only

later may we realise it means something like joy or pleasure. "Beasts and

fowls", too, is a phrase from the Bible rather than a novel. So,

here, we seem to be dealing with things that are not very common in English speaking

countries. (To say nothing of the last word of the first paragraph: Not many

would have expected it to end on "urine". Bloom is introduced by his

predilection and it is, to say the least, one of unusual tastes.)

The second

sentence is interesting, too. Were we to read it aloud, we may find it's not

easy to read quickly, which is due to the numerous consonant clusters. One's

tongue has to run around the palate quite a bit to read it. It is, in Fritz Senn's comparison, a little as though we were

chewing. In other words, the sentence imitates the act of mastication.

A word

about the cat. It says "Mkgnao!" and then "Mrkgnao!"

and again, lowdly, "Mrkrgnao!", as if the cat were emphasising something. On

the one hand, this elaborate attempt to render cat-speech (rather than giving a

simple "miaow") is telling of how closely Bloom is listening (we'll

find him to be a very attentive person indeed). He also tries to imagine

what the cat sees, e.g. whether he looks as tall as a

tower to it, then deciding, "No, she can jump me" (4.29). It's a

trait we'll soon come to appreciate as typical of Bloom, who's often trying to

imagine what the world looks like to others or 'from the other side'. Finally and tellingly in this passage, the cat never

says the same thing twice: it is as though it were giving us a lesson in miniature about how to

read the book in general.

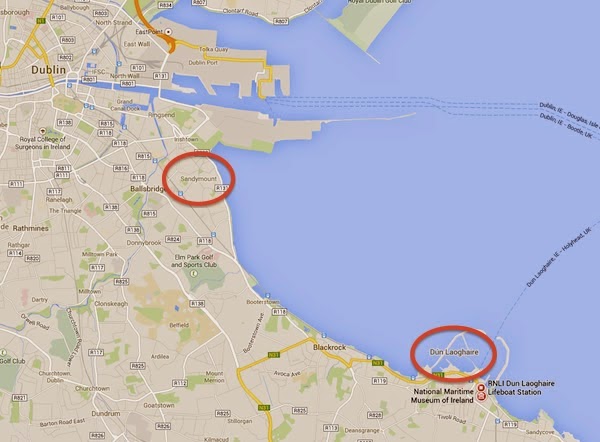

A note about the Home Rule irony that Bloom smiles about, which may need some explanation: On

his way to the butcher's, and walking eastward, Bloom imagines a day in the

Orient, only to conclude, however, that it's "probably not a bit like it

really" (4.99). Similarly, he thinks, "What

Arthur Griffith said about the headpiece over the Freeman leader: a

homerule sun rising up in the northwest from the laneway behind the bank of

Ireland", smiles and, "Ikey touch that: homerule sun rising

up in the northwest (4.100 ff.).

When the Irish were trying to bring on Home Rule to have independent

legislation from Britain, they depicted the Parliament building (which later

became the bank of Ireland) with a sun rising behind it. The irony was that, if you looked

at the bank of Ireland, you'd be facing northwest — which is certainly not where the sun

rises. Our "sun rising up in the northwest" points to how the

symbolism does not match the reality.

So, Bloom's

turning around the image of the orient ("not a bit like it") just as

he considers the twisted political symbolism illustrates how,

often, in Ulysses something is not quite right — a feature that is rather

present throughout the book. It is one worth looking out for and that will add to the humour of the book.